Original article written for SlicingPie.com

One of the often-overlooked features of the Slicing Pie model is the logical outcomes regarding a person’s ability to compete with the startup after a separation. Getting a fair deal for everyone is more than just splitting equity correctly.

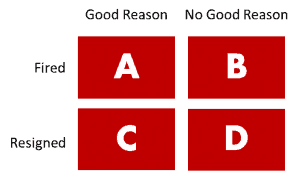

In any company, there are four basic conditions under which a person can be separated from the firm:

- He or she can be fired for good reason

- He or she can be fired for no good reason

- He or she can resign for good reason

- He or she can resign for no good reason

These are universal conditions, although they have different names in different places. In the UK and Europe, I often hear the terms “Good Leaver” for conditions B and C, and “Bad Leaver” for conditions A and D. I also hear fired or terminated for cause or no cause. Use whatever language works, the important thing is that different separation conditions have different logical outcomes when it comes to fairness. The outcomes should always do two things:

- Reflect the fair market value of each person’s contribution. This is their “bet.” Bets are always worth what they’re worth, they don’t have special powers.

- Align everyone’s interests so that each participant has incentives to act in the best interests of the business. No person should ever be given an incentive to act selfishly or greedy.

You can read what happens to a participant’s slices here, but when it comes to whether a person should be free to engage in direct competition with a former employer, it breaks down like this:

If a person is fired for good reason or resigns for no good reason, he or she should not compete with the company or solicit employees. This removes the incentive to deliberately undermine the company’s activities. For example, it wouldn’t be fair for someone to work for a startup during the proof-of-concept stage only to quit and start his or her own company once the business model is figured out.

Conversely, if a person is fired for no good reason or resigns for good reason, the company should not take any action that would hinder the person’s right to engage in competitive activity. The company can, of course, enforce patents, trademarks, copyrights and trade secrets including in-process innovations, customer lists, and other confidential information. For example, it wouldn’t be fair for someone to work for a startup during the proof-of-concept stage only to get fired once the business model is figured out and then preventing him or her from applying his or her skills and knowledge to a new company.

Enforceability

Of course, companies ask employees to sign non-compete agreements all the time and enforceability varies in different states and countries. According to Slicing Pie lawyer, Matt Rossetti: “Non-competes are a severe restriction on commerce and an individual’s ability to make a living. Because of this, the prevailing trend is to limit or bar the enforceability of non-competes.”

But legal isn’t the same thing as fair. It’s important to adhere to what is fair, even if local laws provide opportunities to act unfairly. Just because you live in a place where a non-compete isn’t enforceable doesn’t mean it’s fair to do so.

(I should note, however, that breaking the law should always be avoided.)

The Fair Logic in Action

Merrily and Anson start a lemonade stand and developed a special secret formula for making lemonade.

Scenario One: Anson slacks off on the job and, after two clear warnings, he is fired for good reason. It would not be fair for him to open a competing lemonade stand. If he wanted to be in the lemonade business, he should have corrected his behavior.

Scenario Two: Merrily decides she no longer needs Anson, so she fires him for no good reason. It would be fair for Anson to start a competing stand. If Merrily did not want this, she should have thought twice before firing him for no reason. Anson may not steal the secret formula or any other intellectual property, but he is free to come up with a new formula and go into business.

Scenario Three: Merrily decides they are going to sell kittens instead of lemonade. This is a different business, so Anson would be able to resign for good reason and, as in Scenario Two, would be free to start a lemonade stand. This probably won’t bother Merrily because she abandoned the lemonade concept, but Anson still can’t steal the secret formula. In this case, it would probably be more practical for Merrily to quit the lemonade stand, but she may want to return to selling lemonade, so she wants to retain the trade secret.

Dealing with Ideas

The next two scenarios are common sources of founder disputes because they deal with the idea upon which the company was founded.

Scenario Four (it starts getting more interesting): Let’s pretend that during the planning stage for the business Anson invented the secret formula. Merrily decides she no longer needs Anson, so she fires him for no good reason. It would be fair for Anson to start a competing stand. Anson may not use the secret formula even though it was his idea. The company owns the intellectual property (IP) he developed on the job. Anson will have to come up with a new formula to go into business.

The key legal concept here is called an assignment of rights or work made for hire. Slicing Pie logic assumes an assignment of rights. But all startups should have an assignment of rights contract or at least a clear policy in place.

Scenario Five: Let’s pretend that Anson invented the secret formula prior to starting the business with Merrily who agrees to treat the formula as a trade secret. Merrily decides she no longer needs Anson, so she fires him for no good reason. It would be fair for Anson to start a competing stand. But this does not necessarily mean Anson can extract his IP. In this case, Anson’s rights would be defined by the license agreement he has with the company. If the license agreement was exclusive, he could not use it for his new company, but he would continue to receive the fair market royalties as allocations of slices or cash. If the agreement was non-exclusive, Anson could license the IP to his new company.

Sadly, many founders with pre-existing IP don’t put an agreement in place with the new company. If you feel that you substantially own documented IP upon which a company was founded, it would behoove you to engage an attorney and do a licensing deal with the newly-formed company. This applies to trade secrets, patents, trademarks, and copyrights.

If the fair market value of time and materials were included in the Pie, it should be treated as a work made for hire and the IP would assume to be owned by the company. The owner of the IP should decide, in advance, whether developing the IP was an independent act or simply part of his or her role in the business. In most cases, a person should be able to get slices for time and materials and a royalty.

Startup companies are always changing, but Slicing Pie always delivers an objectively fair deal to participants.

Aligned Incentives

Adhering to the competition logic in Slicing Pie employees think twice before slacking off or quitting and startup managers think twice before firing someone or breaking commitments (which provides good reason to resign). People are free to make their own decisions with full knowledge of the logical consequences that will result. Any agreement that goes against this logic will provide opportunity for one party to benefit at the expense of the other—that’s not fair!